The Differing Ways Educators and Architects Design Learning Environments

To put it mildly, my first few weeks observing and working in the school have been overwhelming. Every day consists of constant exposure to ideas, challenges, questions, and realizations.

From my perspective as an architect, I’ve realized something simple:

When it comes to dictating behavior, educators use words, while architects use environments.

What this implies is that we may be missing an important opportunity if we are not regularly questioning what messages we send intentionally or unintentionally by the way our classrooms are set up.

For example, if an architect designed a sidewalk that is only three feet wide, it will not allow two people to walk side by side – hence making it difficult for conversations. If instead, the path were twenty feet wide, activities such as jogging, biking, gardening, and sitting begin occurring. Finally, at a width of sixty feet, the sidewalk becomes a boulevard that incubates the life one would find in a shopping mall – dining, socializing, performances, resting, vendors, etc… By changing one parameter – width of walkway – a designer can govern the types of activities that occur in the space.

How can a teacher use the classroom to impact children’s behavior? What can we learn from the Reggio Emilia approach regards the classroom environment as the “third teacher” (behind parents and educators).

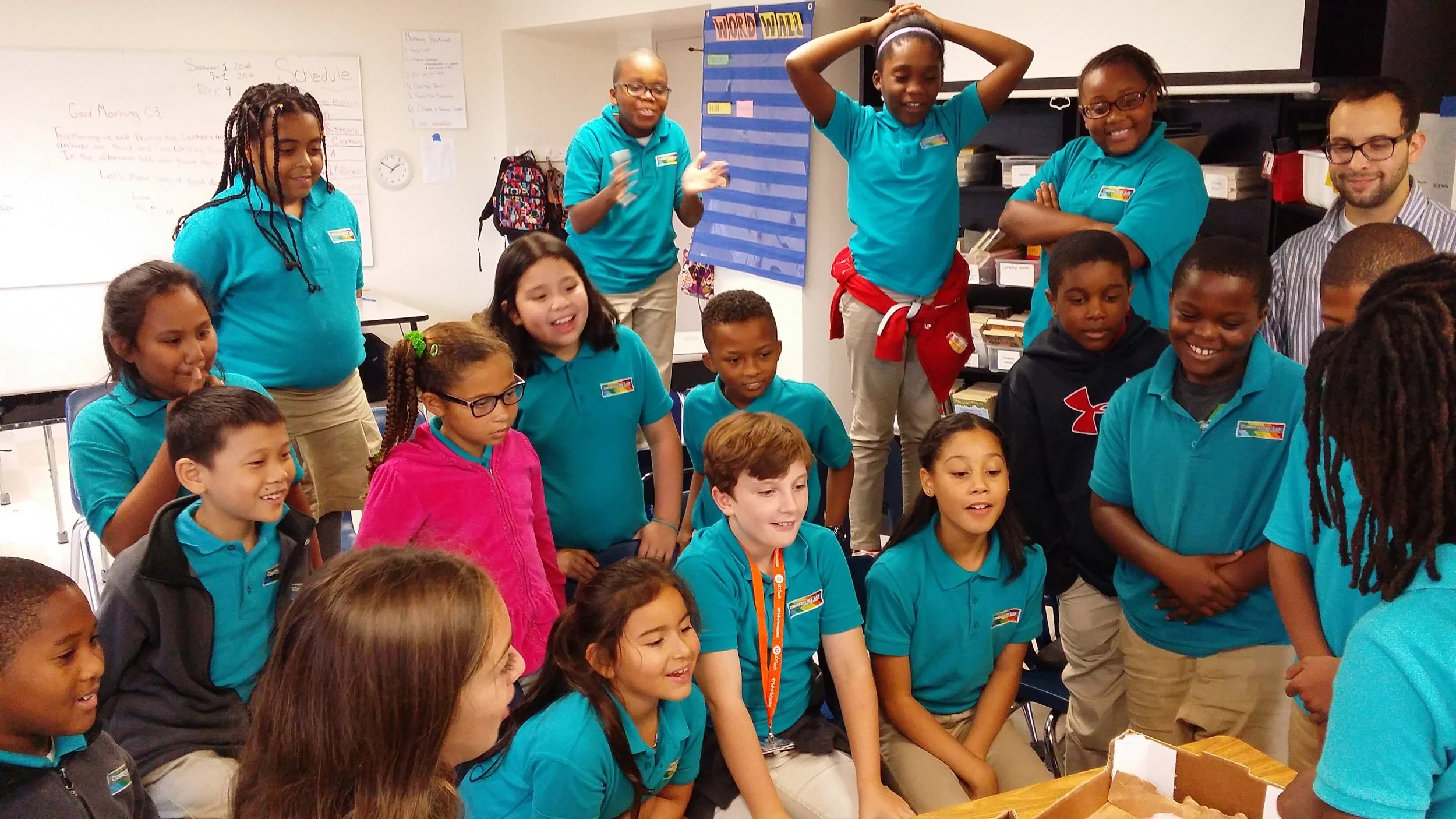

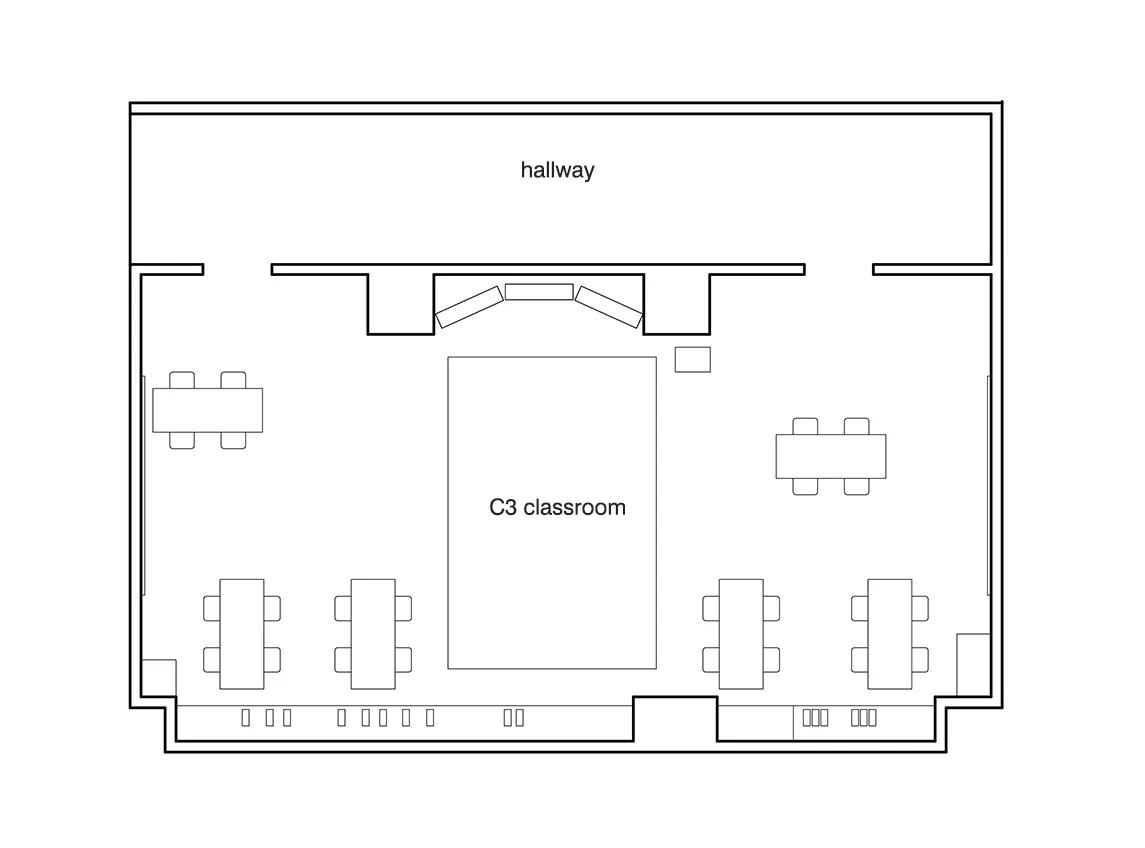

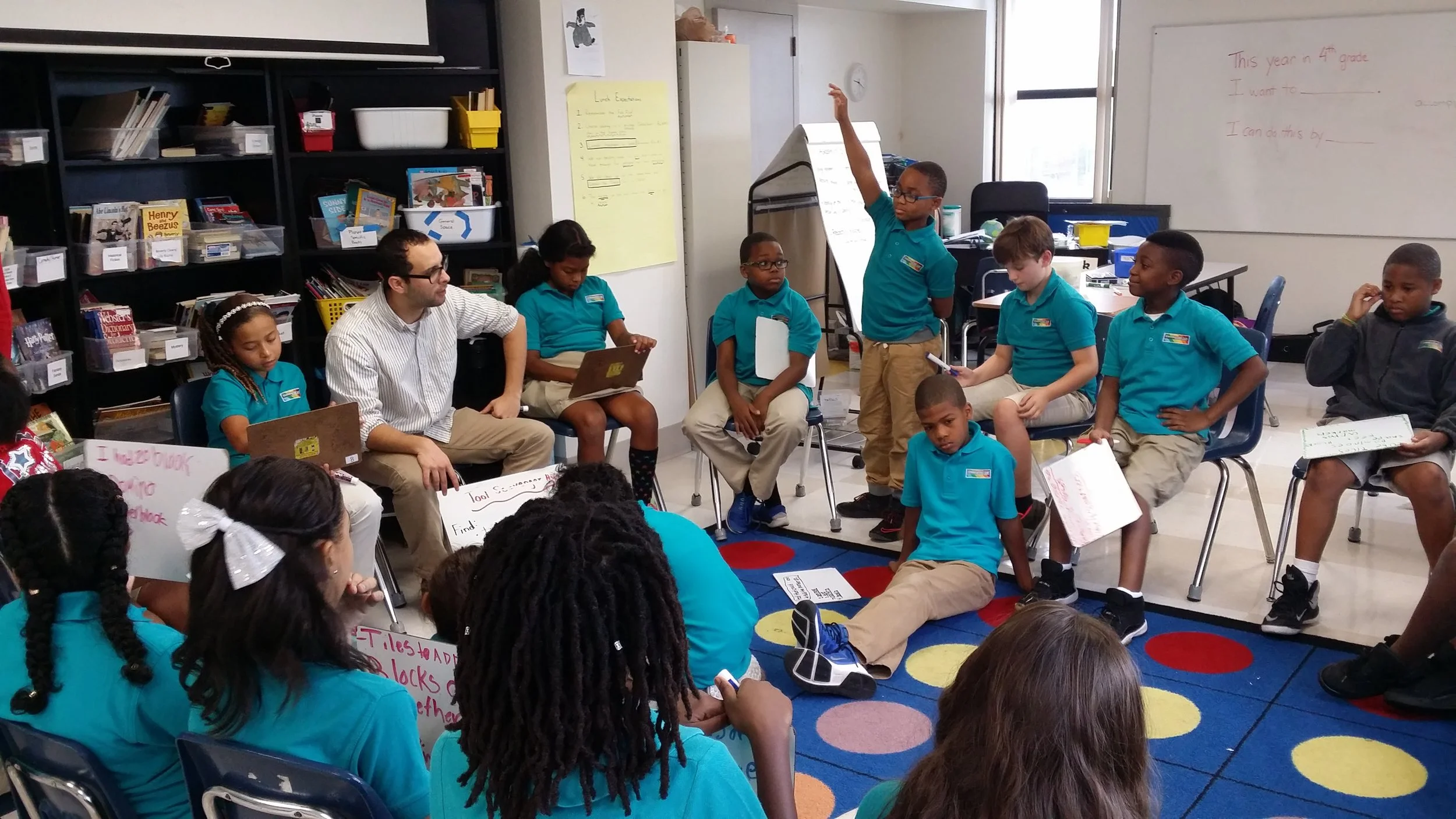

I’ve created a digital model of Mr. Nowak’s 4th grade classroom, which you can view by clicking the box below. Feel free to orbit around this digital space, and—more interestingly—come visit the classroom at C3 on the upper campus!

Clicking on individual numbers will relocate your perspective to specific points in the space, which will help illustrate the particular elements I explore in both this and future blog posts.

This set up is typical of many classrooms, but what messages are being sent to students? Do the elements in the classroom, such as the placement of furniture, posters, desks and materials encourage the type we want from students?

To demonstrate this, let’s take a two-dimensional drawing of Mr. Nowak’s classroom and use it to trace the daily life of an imaginary student named Kevin.

In the morning, Kevin:

1. Walks into the classroom and goes to the wall to hang up his coat and backpack.

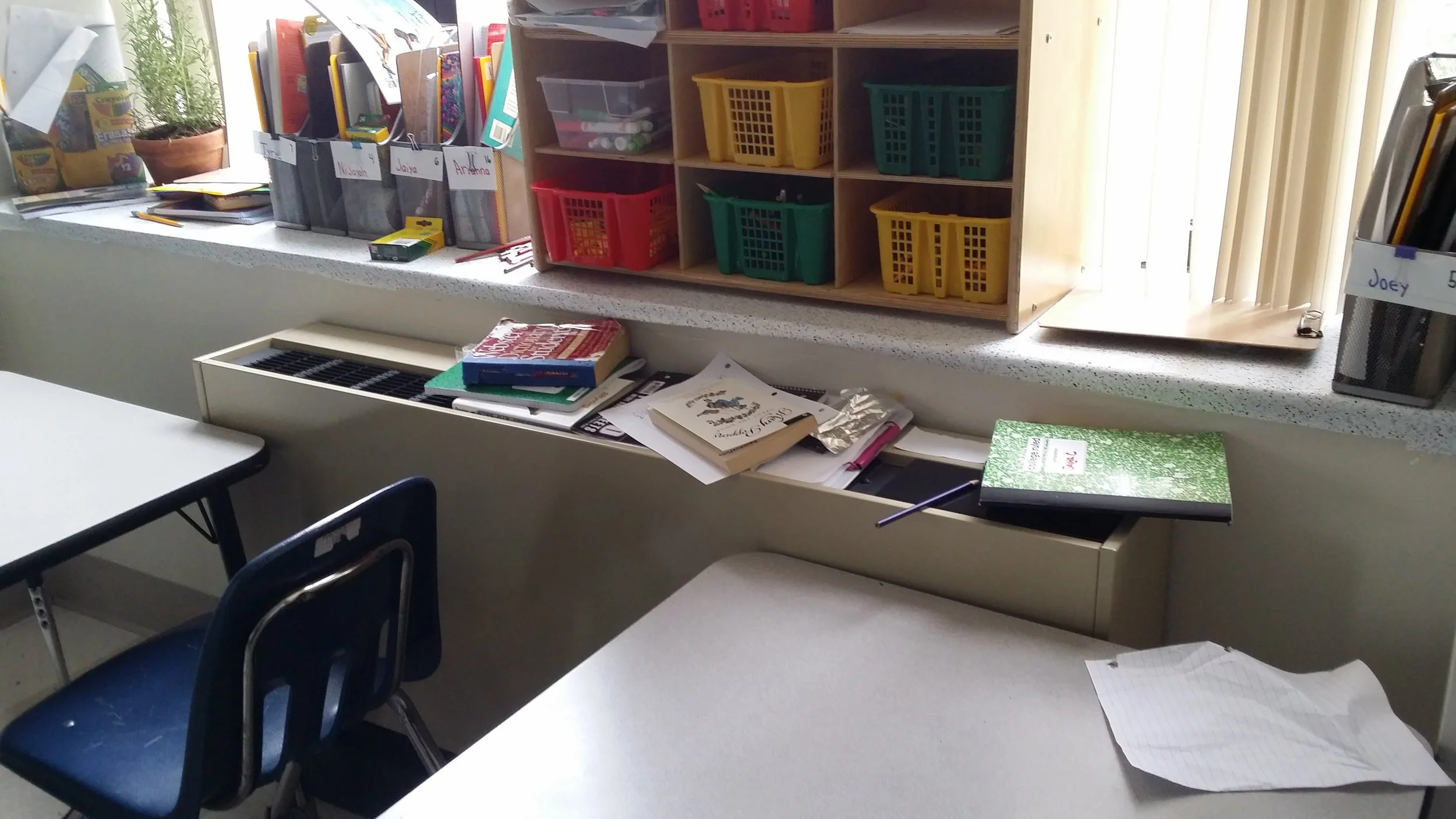

2. Turns around to find the schedule for the day, then proceeds to his desk in the opposite corner of the room.

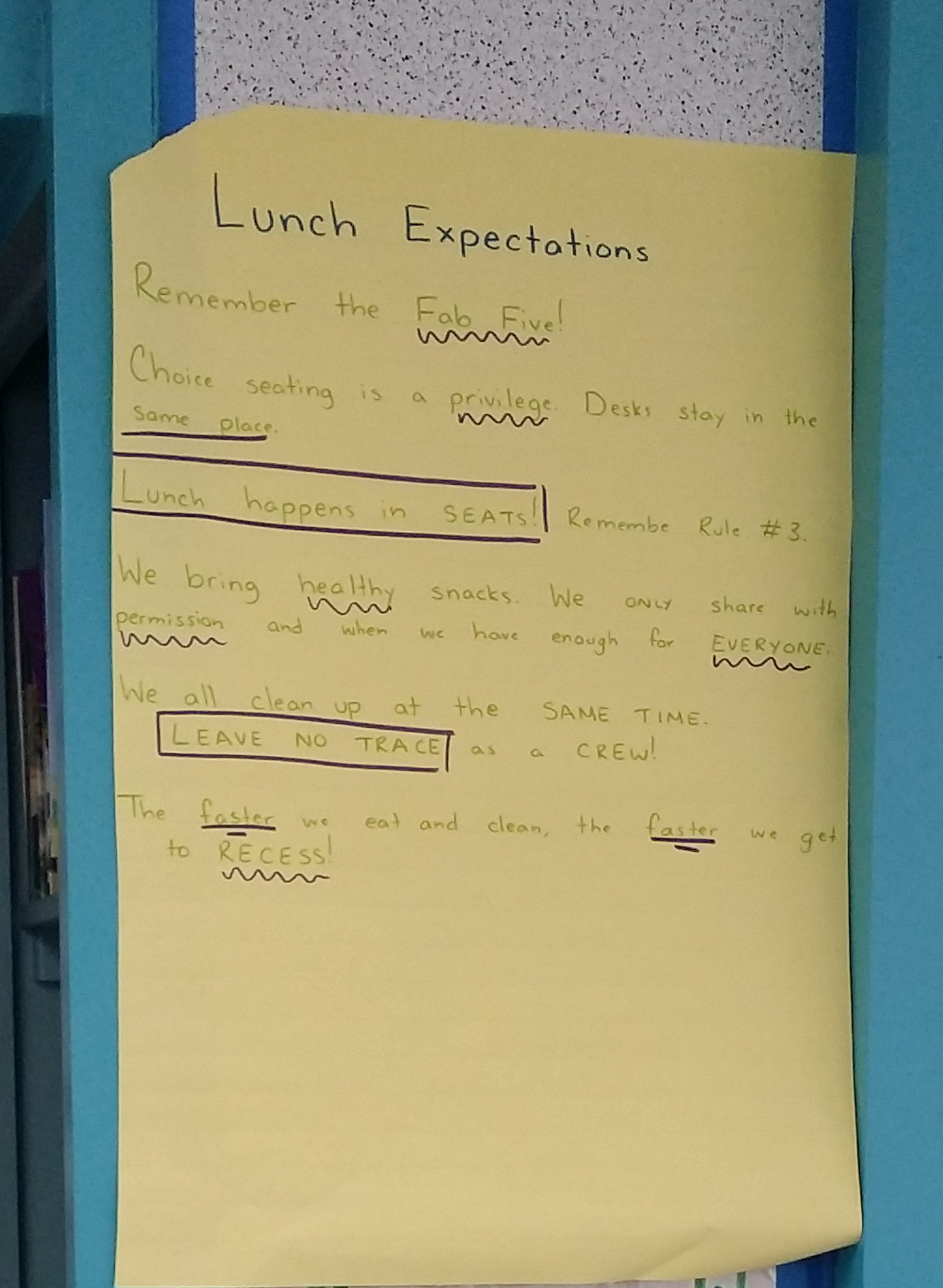

3. Takes down his chair, then must retrace his steps back to the entrance to fetch breakfast, which is part of the morning routine posted on the east column. (For some reason, this routine is different from the lunch one, which is posted on the opposite side of the room.)

4. Heads to the rug with his fellow classmates for morning circle, during which they read the morning message and the learning targets, located on opposite sides of the room.

After gaining an understanding of the day’s structure, Kevin:

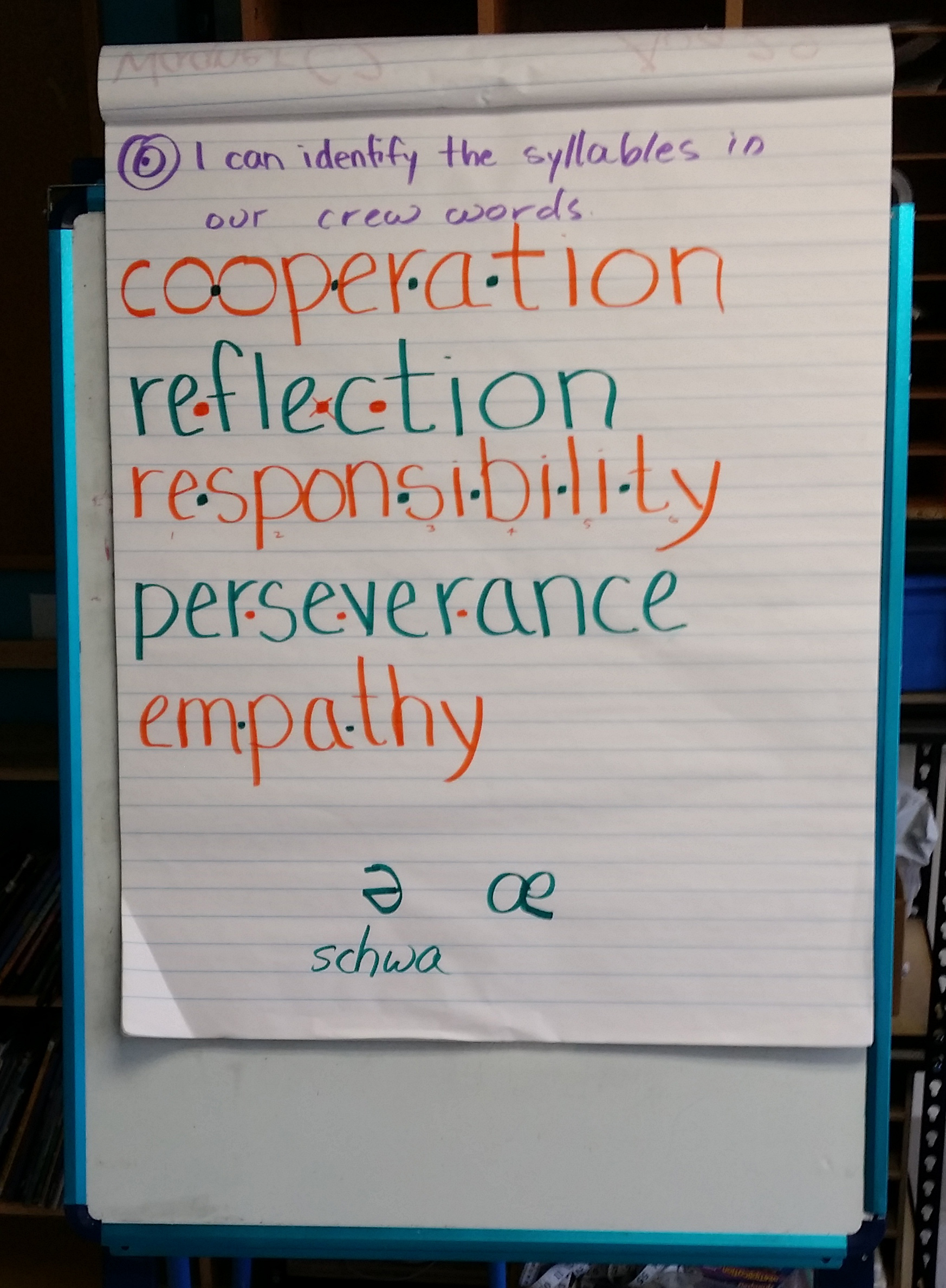

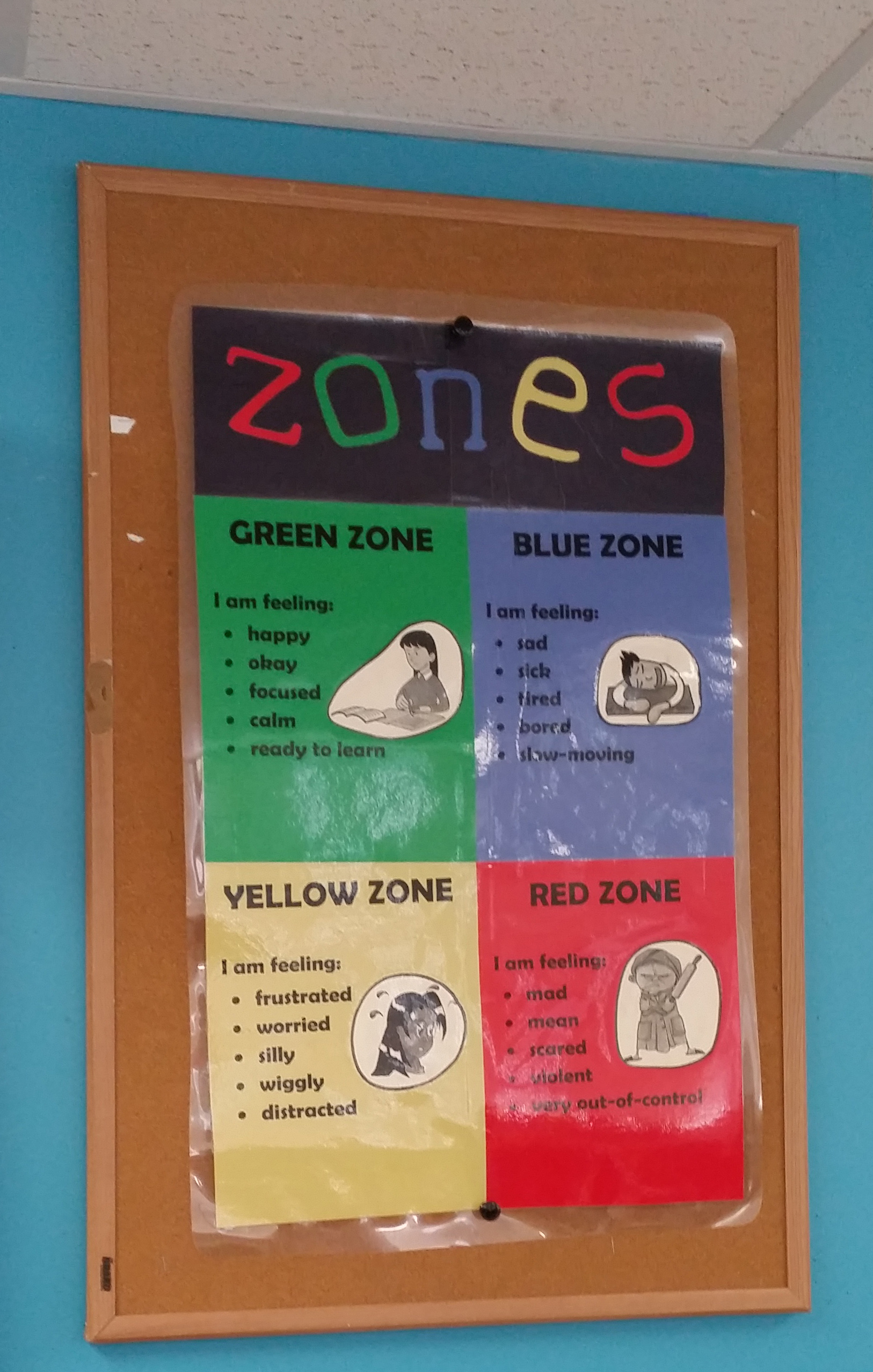

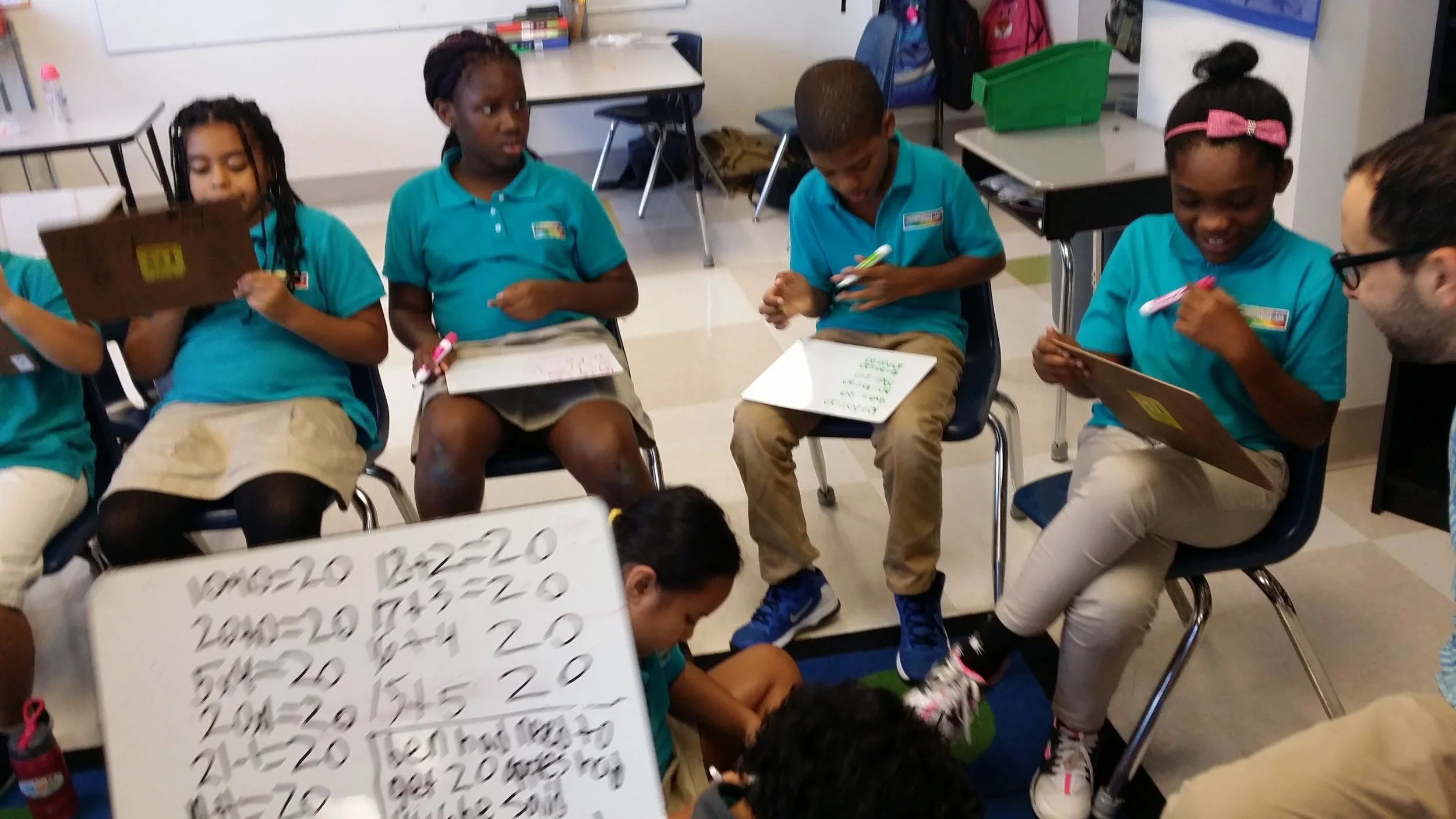

5. Gathers his materials from his bin to go to the learning math station for collaborative work. Inevitably, during this time, the classroom becomes too loud, so the teacher reminds the class of the different zones of regulation and levels of volumes in the classroom, guidelines which are displayed on the west column.

6. Leaves with other students on a break to drink water, which also becomes an opportunity to explore the hallways and return to the classroom via the other entrance, where the trash is “hidden.”

7. Once back at his desk in the classroom, and after making a mess during the morning’s activities, Kevin must traverse the classroom once again to access cleaning supplies before finally putting his work in his cubby, located on the other side of the room.

Remember, these are just one hypothetical student’s movements in the first half of a school day. Compound these by a classroom full of students, over the course of an entire week, and I’m left with a series of intriguing questions:

- What routines and rules that we create verbally are contradicted by the way our classrooms are set up?

- It makes sense that teachers usually engage students with words. After all, that’s how we communicate. But could the classroom environment itself be designed to keep students interested and on track?

- Is the classroom environment directing children’s learning (intentionally or unintentionally), or is it inviting ownership and creativity?

- How can a teacher arrange furniture to reduce both student traffic and visual clutter? Is there a way to rethink classroom organization based on the movements students must make throughout the day?

- How can a classroom alleviate the burden of student management instead of making the problem worse? And wouldn’t most teachers like to free up some extra time for students to really learn?

- What is the environment you do your best learning in and are we creating that kind of environment for our students?

In my next blog, I’ll explore these questions through the different spatial and organizational elements of the classroom and the questions we may want to regularly ask ourselves. ways in which they can be re-optimized.

Please, leave a comment below or send an email to ssun@conservatorylab.org to let me know your thoughts!